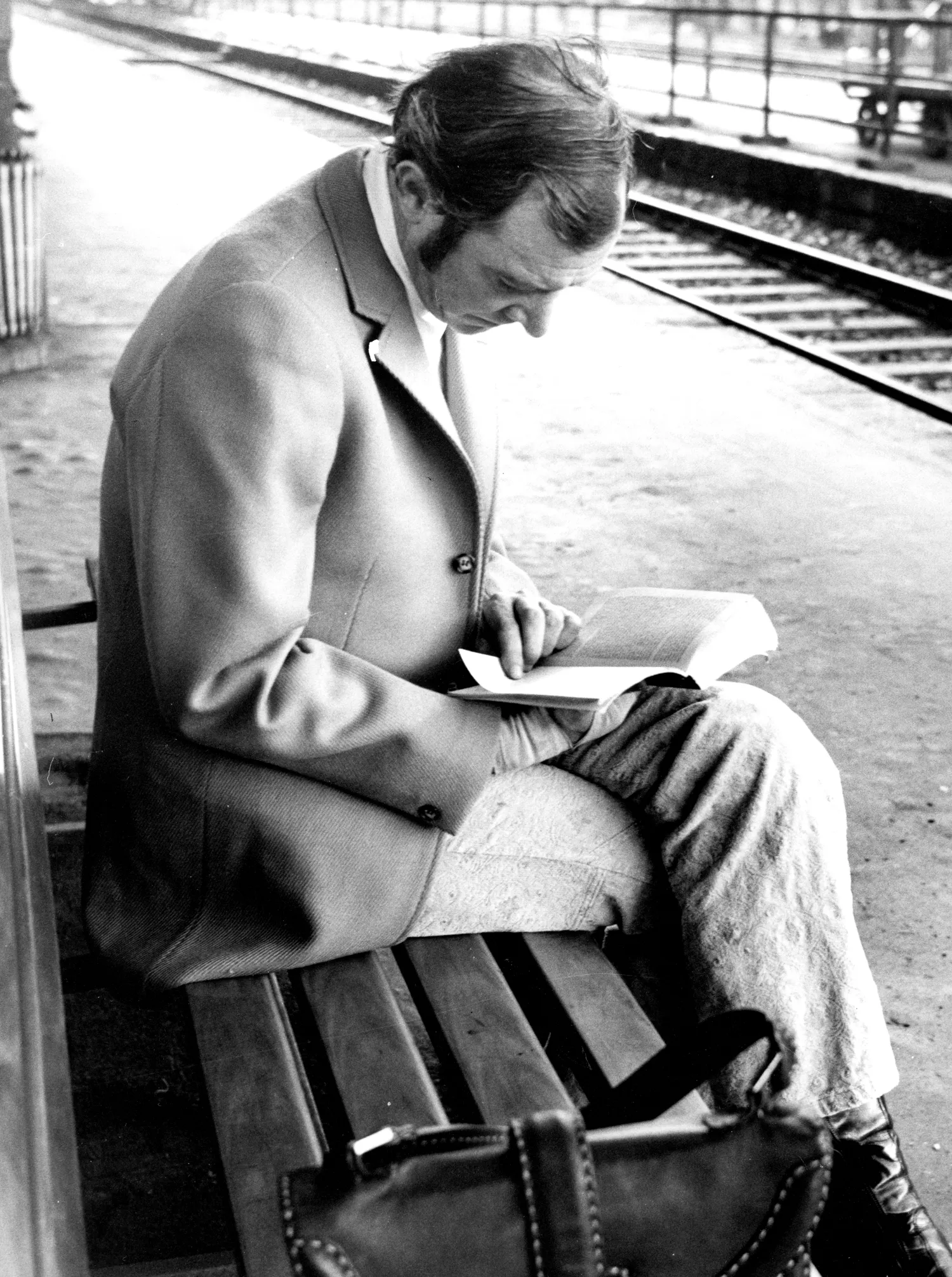

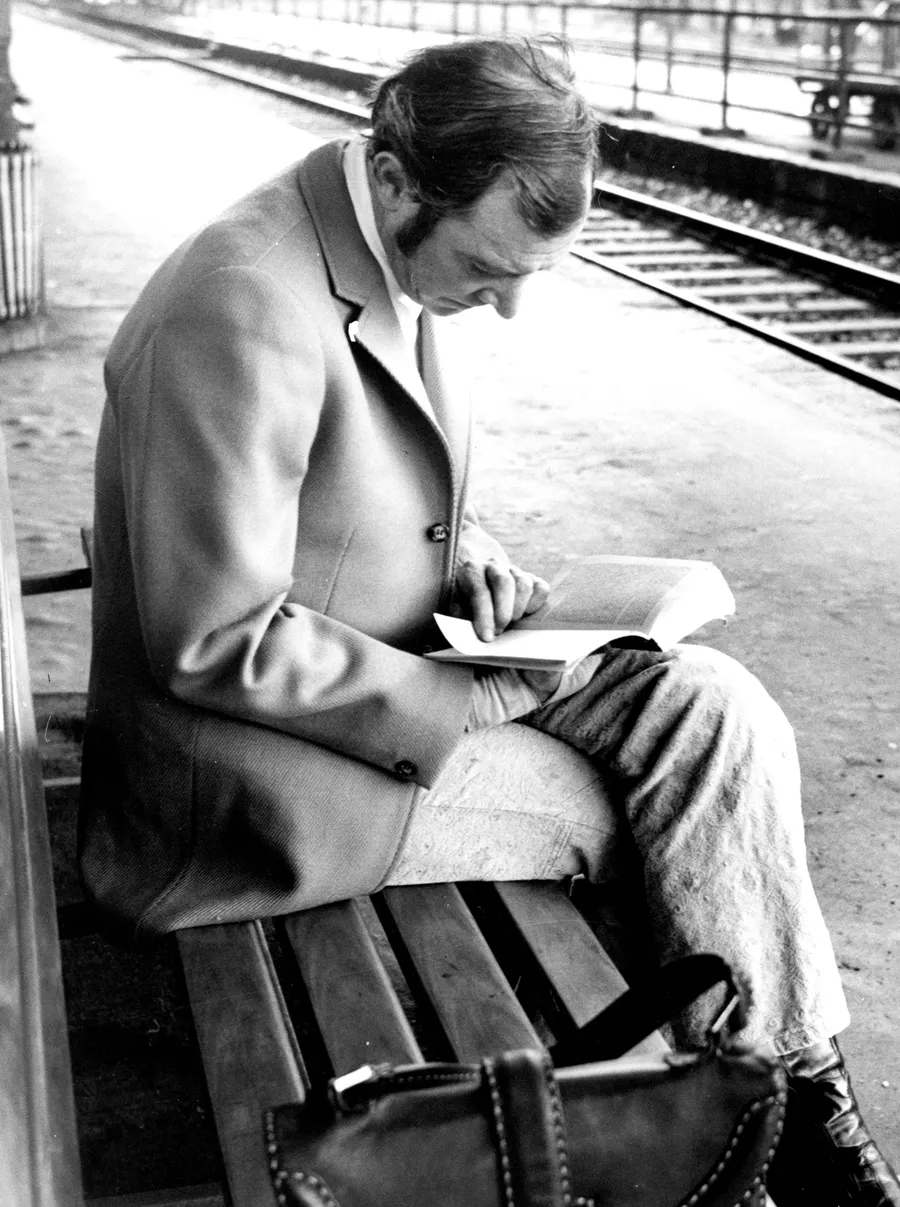

Photo: © Hannes Kilian,

Photo: © Hannes Kilian, courtesy Stuttgarter Ballett/Staatstheater Stuttgart

courtesy Stuttgarter Ballett/Staatstheater Stuttgart

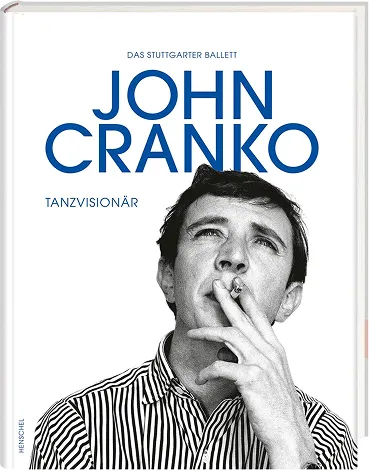

John Cranko

John Cranko (born 15.08.1927, Rustenburg / South Africa, † 26.06.1973 on the return flight from Philadelphia to Stuttgart)

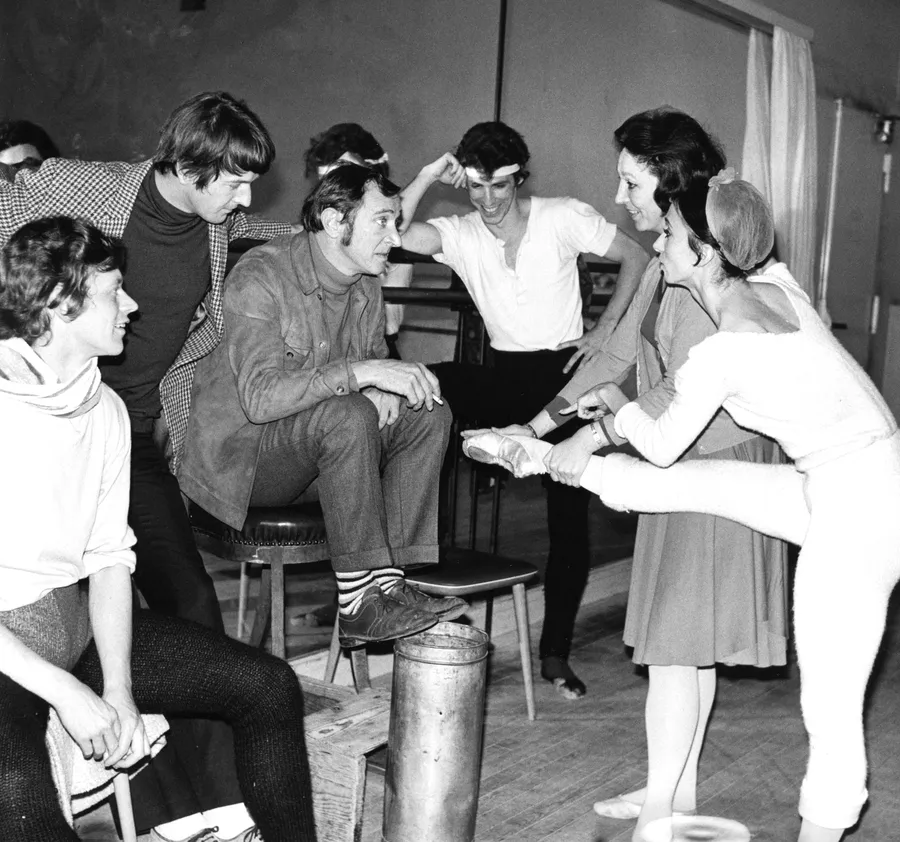

ballet mistress Anne Woolliams and Marcia Haydée, 1969

© Hannes Kilian, courtesy Stuttgarter Ballett/Staatstheater Stuttgart

Who was John Cranko, the man who in just 12 years led the Stuttgart Ballet to world fame, created masterpieces of the 20th century, and pioneered ballet in Germany?

The choreographer who came to Stuttgart in 1961 initially found a modest, little-known “opera ballet company”; upon his sudden death in 1973, he left behind the world-famous Stuttgart Ballet with a repertoire beloved by dancers and audiences alike. These almost unimaginable achievements go back to a person with a far-sighted vision, great warmth, and compelling charisma.

Beginnings

Born on August 15, 1927, in Rustenburg (South Africa), Cranko focused on choreography at an early age. Growing up in Johannesburg, he joined the Ballet School of the University of Cape Town in August 1944 and had already begun choreographic experiments there. His first ballet, The Soldier’s Tale (1944) to music by Igor Stravinsky, was followed by two further works on a small scale before Cranko moved to London in 1946 and joined the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet (today’s Royal Ballet). There he initially worked as a dancer but took every opportunity to choreograph.

Since competition in the British ballet metropolis was fierce, few opportunities presented themselves at first. But with Tritsch Tratsch (1949), which tells—in just three minutes—the story of two sailors vying for a girl’s favor, Cranko had such success that he received further commissions and, in the 1950/51 season, at just 23, was appointed house choreographer at Sadler’s Wells. The subsequent ballets Pineapple Poll (1951) and The Lady and the Fool (1954) for the London company, as well as La Belle Hélène (1955) for the Paris Opera, already hinted at Cranko’s talent for telling stories with complex characters and humor in a convincing way. In 1957, Cranko had the opportunity to create a full-length ballet for the Royal Ballet. He chose what he called a “mythical fairy tale.” The Prince of the Pagodas (1957), to a commissioned score by Benjamin Britten, attracted attention from other ballet companies, which invited Cranko as a choreographer. Among them were the Württemberg State Theatres in Stuttgart, where The Prince of the Pagodas had its German premiere in 1960—shortly before General Intendant Walter Erich Schäfer finally appointed Cranko as ballet director on January 16, 1961.

with Richard Cragun at the MET in New York, 1969

Director and friend

In the following years, the following unfolded from Schäfer’s point of view: “Cranko worked quietly on building his ballet. Until in the fall of 1962, Romeo and Juliet flared up like a meteor, and in a flash the heads of all ballet connoisseurs of the world turned toward Stuttgart, a city that had been dead to ballet for two centuries. And not only did an extraordinary choreography appear, but also an ensemble worthy of the highest regard.” At the beginning of his Stuttgart tenure, Cranko gathered around him a group of dancers who inspired him: in particular Marcia Haydée, for whom he would create the great parts in his narrative ballets, but also Egon Madsen, Richard Cragun, and Birgit Keil—artists inseparably linked with his name and immortalized in the ballet Initials R.B.M.E. (1972). A ballet like an ode to friendship, for his dancers were more than mere employees. Cranko saw great potential in them and trusted them implicitly—even when they themselves did not yet know what they were capable of. According to Haydée, he gave her “the tasks precisely when I was not quite ready,” with the effect that his dancers developed and surpassed themselves. Cranko believed that everyone “carries unique abilities within them that are merely waiting for the opportunity to unfold,” and he had an unfailing instinct for individual strengths. He loved his dancers and, as Haydée put it, “he did not rule by fear but by love.” Through his faith in the dancers and their abilities, he enabled them to achieve the impossible—both technically and dramatically.

Structural improvements

Beyond private matters, the young, committed ballet director campaigned within the State Theatres for his dancers by emancipating the ballet from the opera operation and improving conditions for his ensemble. Dancers no longer had to participate primarily in opera productions but presented their own productions and ballet evenings, and their salaries were adjusted to those of singers and actors—thus, from an initial impulse to help his friends, Cranko set new standards for the German stage landscape. In addition, in 1971 Cranko founded the first state ballet school in the Federal Republic of Germany in order to ensure the long-term supply of talent for his own company. In retrospect, his targeted training of young dancers appears trailblazing, as some companies in Germany followed his example.

Narrative ballets

Young and experienced dancers alike were challenged technically and dramatically in Cranko’s narrative ballets. With Romeo and Juliet (1962)—the work that launched the Cranko era—he showed how craftsmanship and profound expression can be united at the highest level. In the ballet based on William Shakespeare—his favorite author—the choreographer demonstrated his talent for telling a story purely through movement with nuance and coherence. Cranko created complex characters who, in a comprehensible plot, pass through different phases of life and emotion. For Cranko, perfect dance technique was not the primary goal; he valued expressive quality and therefore worked relentlessly on details and dramatic subtleties. He likewise demonstrated the genius of his dramaturgy in Onegin (1965; revised 1967), after Alexander Pushkin’s verse novel, and in his version of Swan Lake (1972). Yet Cranko did not restrict himself to a single genre; he mastered the tragic as well as the comic—a genre few choreographers dare to approach. Above all, in The Taming of the Shrew (1969), after Shakespeare, he showed how humor can be reconciled with artistic ambition.

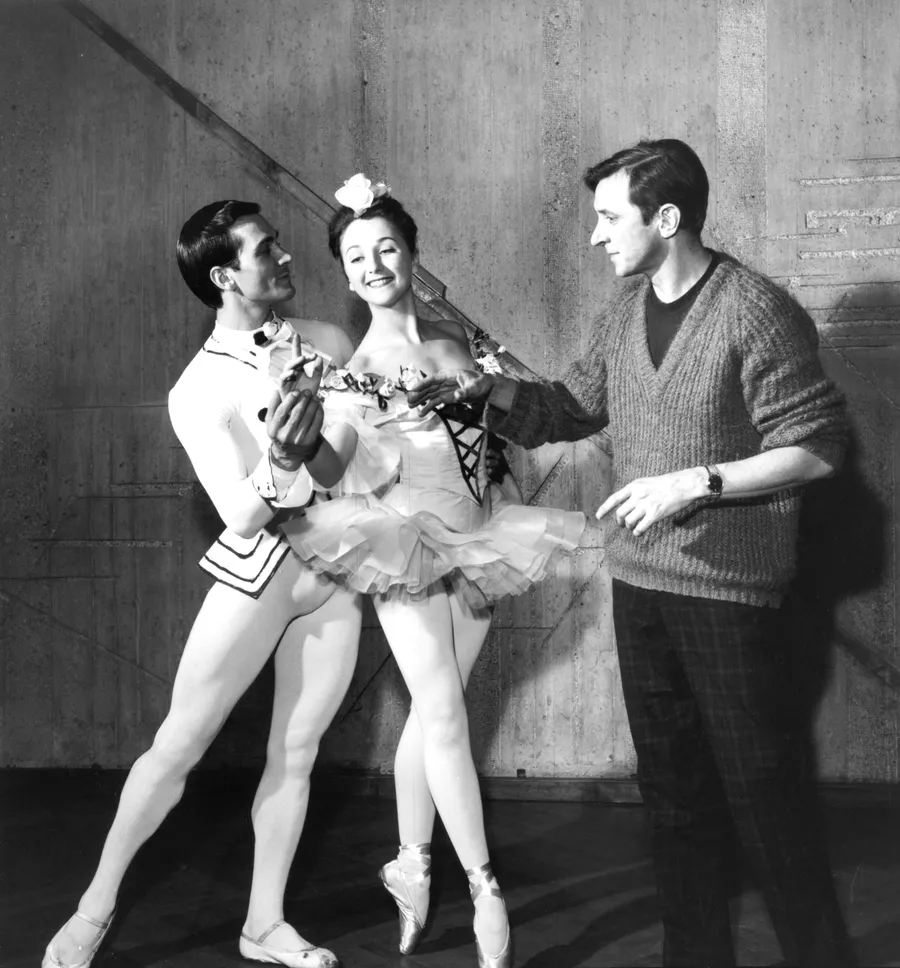

Alfredo Köllner, Micheline Faure, John Cranko

© Hannes Kilian, courtesy Stuttgarter Ballett/Staatstheater Stuttgart

Out in the world

Cranko’s The Taming of the Shrew (1969), alongside his two other large-scale narrative ballets Romeo and Juliet (1962) and Onegin (1965; 1967), is now danced not only by the Stuttgart Ballet; all three have entered the repertoires of the world’s most important ballet companies—especially Onegin, which is now considered a classic of the 20th century. Cranko would surely have been delighted, as he saw international recognition as a seal of quality. But he did not only send his works out into the world; he also sent his company. Already in the 1960s, he took the ensemble on tour, convinced that “a company must travel; it must be seen—by different audiences that react differently—and the dancers must learn to adapt to different stages.” The first major tour took the as-yet unknown ensemble to New York in 1969—then a ballet metropolis and cultural hub. The dancers stepped onto the stage knowing that they would have to return home immediately if the audience did not applaud enthusiastically. But it was a breakthrough! The audience was thrilled, the New York Times critic Clive Barnes proclaimed the “Stuttgart Ballet Miracle,” and the company—overnight famous—stayed for three weeks in New York, giving 24 sold-out performances. The troupe was subsequently invited to perform around the world. To this day, the Stuttgart Ballet travels the globe—from Asia to neighboring European countries to North and South America.

Between abstract and narrative

In addition to full-length ballets, Cranko created a number of shorter choreographies: Jeu de cartes (1965), Opus 1 (1965), The Inquiry (1967), Présence (1968), and Brouillards (1972) are among the pieces with which Cranko moved between the poles of the abstract and the narrative. At one end of the scale stands the witty Jeu de cartes, inspired by a card game. At the other end are symphonic ballets such as L’Estro Armonico (1963), Concerto for Flute and Harp (1966), or Initials R.B.M.E. (1972), in which Cranko immersed himself in the music and translated it into dance form. Between abstract and narrative lies Brouillards, in which the audience is presented with suggestions of scenes from everyday life, humanity, and nature. In his last work before his death—Spuren (1973)—Cranko addressed the themes of dictatorship, flight, and new beginnings—a piece at once political and moving, set to the Adagio from Gustav Mahler’s 10th Symphony.

Artistic collaboration

The lasting success of Cranko’s works is due primarily to his timeless choreographies, but music and design also contribute to the Gesamtkunstwerk. Cranko relied on teamwork and, as he said, “the collaborators’ faith in one another.” When, in 1962, he entrusted the then 25-year-old Jürgen Rose with the designs for his Romeo and Juliet, a creative partnership began that continued successfully with Swan Lake (1972), Onegin (1965; 1967), Poème de l’Extase (1970), Initials R.B.M.E. (1972), and Spuren (1973). Cranko also placed his trust in the composer and conductor Kurt-Heinz Stolze, who arranged the music for Onegin and The Taming of the Shrew (1969). In addition to his own choreographic work, Cranko gave other choreographers scope—and together with the Stuttgart-based Noverre Society, he even encouraged dancers with promising interest to create their own works, such as the now-famous choreographers John Neumeier and Jiří Kylián, both dancers under Cranko in Stuttgart. From his own experience in London, Cranko knew how difficult it was for young artists to experiment choreographically. He was convinced: “There must be a charitable organization willing to provide dancers with rehearsal opportunities and a theatre. Ballet must be seen; it does not exist if it is not seen.” For this reason, he generously supported others—especially young choreographers—and, together with Fritz Höver, chairman of the Noverre Society in Stuttgart, established Europe’s first “Young Choreographers” platform in 1961.

© Hannes Kilian, courtesy Stuttgarter Ballett/Staatstheater Stuttgart

Life

Cranko lived as intensely as he worked, devoting himself completely to whatever aroused his interest. To satisfy his enormous thirst for knowledge, he immersed himself in literature and music. He met people with the same genuine interest. In this way, he left a strong impression not only on his closest collaborators but also on the people of Stuttgart. Cranko was a star of the scene, who mingled with the public and stood out for his extravagant clothing and his openly lived homosexuality. He loved to turn night into day and was known for celebrating in local venues. Members of the company were his friends, with whom he went out and spent time away from the ballet studio. In private, however, Cranko did not find happiness and suffered from loneliness. He had depressive phases, was melancholic, and drank too much alcohol. Yet this is not what his companions remember. They remember him as a warm-hearted friend, a sensitive person, and a brilliant artist who always had an open ear for them.

Cranko’s legacy

On June 26, 1973, Cranko died suddenly on the return flight from New York to Stuttgart. His legacy is manifested not only in his choreographies—which to this day constitute a cornerstone of the Stuttgart Ballet’s repertoire and are indispensable to the international ballet canon—but also in the school he founded; the “Young Choreographers” platform he helped establish; the emancipation of ballet from the opera apparatus; and the establishment of ballet as an autonomous, equal art form in Germany.

Learn more about John Cranko

John Cranko - Tanzvisionär

Available here

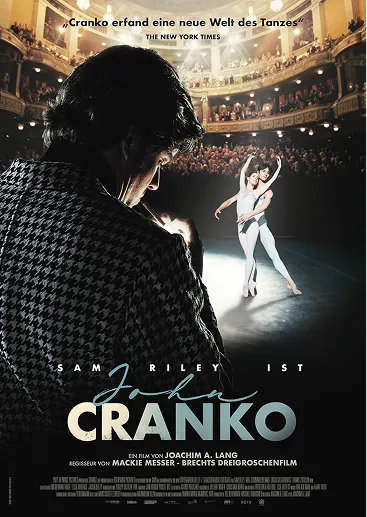

Cranko

Drama / 2024

Director: Joachim Lang

Watch here